| 1 : 1939 - Germany & Russia Attack Poland | 4 : Back to Work | |

| 2 : The Train to Russian Internment | 5 : 1941 - News of Release | |

| 3 : A Stay in Hospital Near to Death | 6 : Imprisoned Again |

2 : The Train to Russian Internment |

|

The train began to move, and as if on command, the whole train began to sing "Rota", a historic Polish patriotic form of an oath: |

|||

We

won't forsake the land of our birth, We

won't forsake the land of our birth,We won't let them bury our language, No German will spit in our face And germanize our children. We, the Polish are a nation, of Polish kin That stems from the royal tribe of Piast. To

the last drop of blood in our veins Every home

shall be our fortress. |

|||

"Anoka nie ary, anoka nie ary" (Do not shout, don't shout) yelled the Russians. But no-one took any notice, and the train left in a hurry. The train went through Bialystok, Wolkowysk, Baranowicze, Mikaszewicze on to Bobruysk in Byelorussia. When going through Bobruysk, I remembered that my father was wounded there in the war with Bolsheviks in the 1920. Next was Minsk and finally Gomel near the Ukraine. At Gomel the train stopped and we were taken out in groups of fifty and led to Gomel prison. It was a grim sort of prison. We were taken out to the prison yard, segregated and led to the cells. It was here that I saw the biggest rats ever, running on top of the wall. They were feeding on corpses in the mortuary. The cells were small, about 4 x 5 metres. We were packed in like sardines, fifty to a cell, and had to lay down in three rows. No one could turn around, unless the whole row was turning. Here we were given ten minutes of exercise in the yard each day. We had to go down winding stairs to get to the yard. A number of people couldn't take it anymore and committed suicide by jumping down from the stairs, head first. So the prison staff put up wire netting on the banisters to stop it. They needed slave labour. They brought in several Germans from Siberia, who were settled there by czar Nikolay Romanov to teach the natives to farm properly. The Germans were solid sort of men and they got on well with us. * * * |

In the cells we were talking about our hopes for the future, our families, our dreams and about food, as hungry people always have food on the mind, and we had nothing but contempt for the Russian. And we never lost hope. One day there was a lot of activity in the yard. One man tried to escape, by hiding in one of the outbuildings, hoping to scale the wall at night, but the dogs had tracked him out and he was caught, beaten up and put in a penal cell and had his food reduced. I met him later on. His name was Zewuski and he was a historian. Then the epidemic of dysentery broke out and everybody had it sooner or later. The worst affected were taken to hospital located on the ground floor. They were stripped naked and were given a blanket to cover themselves. This was done to prevent escape, as it was possible to jump out from the toilet window on to the wall. At the beginning of August 1940, they started to take us to one of their offices, where several NKVD officers were sitting at the table. When I was taken there, one of them read out my sentence: "Grazhdanin Polkovski Frants Viecheslavovich - asuzhdonyi osobiennym sovieshchaniem na tri goda ispravitsielnykh lagierej, z napravleniem - Sieviernyje Zhelezno Dorozhnyje Lagiera, Kotlas. - Podpishi!" (Citizen Polkowski Franc son of Czeslaw, sentenced by special sitting to three years of corrective camps, with the destination Northern Railway Camps - Kotlas. Sign!). When I refused to sign, he just said: "Podpishish ili nie podpishish, siediets budiesh" (Whether you sign or not sign, you will do time!) and he signed the paper himself. After that jest, I was taken to a different cell where I met my cousin Edward Rymaszewski. He jumped up to me calling - "Mietek! Mietek!". I had to stop him calling my name, and told him my adopted name: Franek Polkowski. From then on we were together for the rest of our captivity. On 21 August 1940 we were sorted out into groups of fifty, escorted to the railway station and put into cattle trucks.

We could hear Russian soldiers

singing songs like: "Rastsvitali jabloni i grushi, popllyli tumany

nad rekoi, vykhadilla na biereg Katiusha, na vysokij, na biereg krutoi",

and "Tri tankista, tri Somewhere between Leningrad and Kotlas, there was an attempt to escape. One Bielorussin managed to cut a hole in the floor of the truck, with a piece of flint, big enough to get through. He then dropped between the rails and waited till the rest of the train passed over. Unfortunately the guards saw him and stopped the train, picked him up, beat him black and blue and put him in a special truck. They checked all the trucks and the train moved on to Kotlas. At Kotlas the train stopped, we were taken out in groups of fifty and escorted to the camp. The camp consisted of a few huts, surrounded by high barbed wire fence with a tower at each corner, manned by soldiers with rifles and machine guns. Inside the camp, the mud was knee deep, having been stamped by thousands of feet. After a few days there, we were again sorted into groups of fifty, and escorted through the taiga to the river Northern Dvina, about 8 km away.

After a few days the barges stopped and we were escorted to a new camp. * * * |

|

Each small group had to build their own shelter. Being brought up in the forest I have made a safe shelter, but many others who had no idea how to build one, have paid with their lives, as the shelters collapsed on them during the night. In the morning we woke up with one side frozen to the ground, the other covered with snow. Winter was approaching in that area. A group of us decided to escape, while we were in the taiga to collect firewood. The day we were going to run away, I awoke to find my legs swollen so much that flesh was hanging over the leggings of my boots. Malnutrition, and lack of vitamins had done its work and I was struck with scurvy. I realised that I would not be able to go in this condition, so the attempt to run away was abandoned. Later on we learned to fight scurvy by boiling pine and spruce needles and drinking the brew. We also started to boil willow bark and twigs as a substitute for aspirin and twigs of bilberries to cure diarrhea. The water from the ditches started to overflow and mix with the drinking water, and dysentery struck. Some of us managed to avoid it, by drinking only water from melted snow.

Estonia was a small country with a small navy, so they selected sailors of good appearance and intelligence, as every sailor was their ambassador. Strong, healthy young men, needed food, but they didn't get it and they were the first to die. Next to die were the old and the weak. There was a group of Lithuanians in the tent, and they too died soon. The last one died with his head frozen to the tent, as their breath was condensing and freezing on the cloth of the tent. In that camp, only 60 men were left out of 360, from November 1940 to February 1941. In the next tent there were Russians. Often they would ask us about life in the West and did we have "disin-cameras"? (An air tight container, used for disinfecting and delousing clothing with hot steam). When the answer was no, they would say you have no culture, as they could not accept that people could be free of lice. Our work was to build the railway line from Kotlas to Vorkuta. We had to dig soil from the hills and take it onto the embankment in the wheelbarrow. Everybody had to take a number of cubic metres of soil; if you couldn't your food would be reduced. We were getting 300 grams of bread a day and some watery soup twice a day. Malnutrition, hard work and exposure to sub arctic climate took it's toll daily. On one occasion, after a heavy snow fall I had to take soil from a high embankment, so I went around to clear the snow. Having done this, I jumped down into deep snow below. One of the guards saw me falling and thought that I had fallen down by accident. He came over and asked if I was hurt? I said yes, I was hurt. He then called two other men and told them to take me to the camp. He was one of the humane Russians, quite a rare individual in this service. He even offered me some "karashki" (crushed tobacco stalks, smoked by poor Russians). So I had a few days off work, and by going to help in the kitchen, I managed to get some salted fish, which I shared with my cousin Edward. * * * |

|

After a few days of rest, I had to go back to work and noticed that one of the railway supervising technicians, a Russian, was watching me, or rather my boots. That night he came over to see me and asked if would sell him my boots and my jacket as he was going to be freed soon (he was a prisoner too), and would like to make a good pair of boots when he got home. The leather of my boots was very good and being hunting boots with high leggings, there would be enough of it to make a complete pair of normal boots. As for the jacket, although it was torn, it was made of good cloth and would make a very good cap. In the West no one would touch it, as it was dirty and lousy, but to him it was a really valuable item. Knowing that if a Russian wanted something, he would get it, even if he had to kill for it, I agreed. He gave me a pair of moccasins made out of an old lorry tyre, an old Russian coat and a piece of bread as well as a few rubles, and he was pleased with his purchase. Later on he came over again and asked if I could write in Russian. I said yes, I could. Then I will make you "atmietchik'om" (checker). Next morning he gave me a piece of plywood, a pencil, a piece of glass and a ruler. I was to measure the contents of all the wheelbarrows and book it against the name of the man who brought it in, so that they could decide how much bread he would get, as everybody had to bring in so many cubic metres of soil. So my work was much lighter. Next day I spotted one Russian official hiding behind some trees and writing something down. I realised that he was checking up on me, so I booked everything exactly. After some time he came over and measured up the contents of a few wheelbarrows, then compared my booking with his. Everything was correct. After that, I was adding as much as I could for everybody, but always watchful. However, later on we heard that six million of cubic metres was over-booked and two Russian engineers were shot for it. We moved camp again, further North. Here we saw Russian gangs building "lezniovka" (a road made of double rafts). They would hew one side of the logs, and pin them down to sleepers to form a double raft. When snow had covered them up, they would roll the snow down and pour water on it. When it was frozen they would sprinkle grit over it, and the road was ready to take lorries carrying rails. |

|

|||

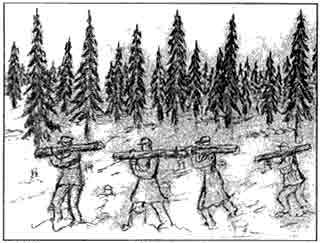

Hard manual labour in taiga |

||||

Here we had to walk 3 km to a place where it was proposed that a station be built, and cut down trees to make firewood for locomotives. To the South of us there was a camp, number 8, housing Russians who refused to work. Russians called it "shtrafnaya collona" (penal camp). To the North of us was camp number 11, holding Polish prisoners of war, still in their uniforms. Among us was an ex-sergeant of the Polish frontier defence corps (K.O.P.) by the name of Franciszek Lewandowski, stationed in Hancewicze. He got ill and refused to go to work one day. The Russian guards dragged him out, tied him to a sledge and dragged him 3 km to work, where one of them kicked him, saying "davai podnimaisia" (come on, get up). But Franciszek Lewandowski was dead. The Russian gave a sheepish grin and told others to take him away. Gradually the trees between the camps were cut down and we could see the two camps numbers 8 and 11. One morning we heard machine gun fire coming from camp number 8 and we could see the inmates of that camp being machine-gunned from the towers. We understood that 800 men were murdered there. On one occasion they brought a group of Armenians straight from the Black Sea region, dressed for a hot climate, straight into the sub-arctic. They were very cold, so they gathered some firewood, lit up a little fire and squatted around it, and as the fire died down they started to drop backwards - dead. Within a short time they were all dead. On a few occasions when the temperature was below minus fifty five degrees Celsius (i.e. centigrade), the commander of the guards would refuse to supply an escort for the prisoners and we would have a rest. |

| 1 : 1939 - Germany & Russia Attack Poland | 4 : Back to Work | |

| 2 : The Train to Russian Internment | 5 : 1941 - News of Release | |

| 3 : A Stay in Hospital Near to Death | 6 : Imprisoned Again |

This

time the train was even longer. Two locomotives in front and two in the

back. The train went through Minsk to Smolensk. While going through Smolensk,

I remembered that my grandfather was wounded there in the first world

war. The train was going North towards Leningrad and Kotlas. At one time

we were going through a burned out taiga, stretching for over 100 km.

All along the way, our train stopped occasionally to let the military

trains through.

This

time the train was even longer. Two locomotives in front and two in the

back. The train went through Minsk to Smolensk. While going through Smolensk,

I remembered that my grandfather was wounded there in the first world

war. The train was going North towards Leningrad and Kotlas. At one time

we were going through a burned out taiga, stretching for over 100 km.

All along the way, our train stopped occasionally to let the military

trains through.  viesiollykh

drugov, ekipa z'mashyny bojewoi" and "Hey tachanka rostachanka,

vsie chetyiri kolesa". And of course their classic: "O Kalinka,

Kalinka moya, rozkudravaia malinka, malinka moya, polubilazh ty mienia".

viesiollykh

drugov, ekipa z'mashyny bojewoi" and "Hey tachanka rostachanka,

vsie chetyiri kolesa". And of course their classic: "O Kalinka,

Kalinka moya, rozkudravaia malinka, malinka moya, polubilazh ty mienia".

There

we were escorted onto barges, and sailed North for a few days, stopping

at night. We were given three hundred grams of bread and a small piece

of boiled fish. One of the men picked up a piece of tin and used it to

cut fish. Russian in charge of the barge saw it from top deck, came down

and kicked him black and blue, while the guards were watching from the

top, with the rifles at the ready. The Russian was tall, ginger headed,

a really evil savage monster.

There

we were escorted onto barges, and sailed North for a few days, stopping

at night. We were given three hundred grams of bread and a small piece

of boiled fish. One of the men picked up a piece of tin and used it to

cut fish. Russian in charge of the barge saw it from top deck, came down

and kicked him black and blue, while the guards were watching from the

top, with the rifles at the ready. The Russian was tall, ginger headed,

a really evil savage monster.  It

was an empty square piece of ground, cleared of trees, surrounded by a

high barbed-wire fence with a tower at each corner and two ditches, one

for the latrine the other for drinking water. After

a while an official came in and picked out a number of men, including

myself, and led us to the gate. We were given some tools and were escorted

into the taiga, where we had to cut down some trees for building shelters

and fires.

It

was an empty square piece of ground, cleared of trees, surrounded by a

high barbed-wire fence with a tower at each corner and two ditches, one

for the latrine the other for drinking water. After

a while an official came in and picked out a number of men, including

myself, and led us to the gate. We were given some tools and were escorted

into the taiga, where we had to cut down some trees for building shelters

and fires.  After

a few weeks we were moved to another camp, and were given the number 21,

which applied to us as a group of slaves, not the camp itself. This time

there were some shelters, in the form of marquee type tents pulled over

wooden framework. Inside the tent, there was a small metal stove and some

firewood. One man was to keep the fire going and the tent tidy. In our

case Mr Moszko was appointed, whom I later met as staff sergeant in the

army. In one corner of the tent there was a group of Estonian sailors.

They often sang and their favourite song was Tango nocturne, which they

sang in Estonian.

After

a few weeks we were moved to another camp, and were given the number 21,

which applied to us as a group of slaves, not the camp itself. This time

there were some shelters, in the form of marquee type tents pulled over

wooden framework. Inside the tent, there was a small metal stove and some

firewood. One man was to keep the fire going and the tent tidy. In our

case Mr Moszko was appointed, whom I later met as staff sergeant in the

army. In one corner of the tent there was a group of Estonian sailors.

They often sang and their favourite song was Tango nocturne, which they

sang in Estonian.